Materials

The exhibition assembles research output by contemporary designers working in material experimentation. These are organized around five “material acts”: Re-Fusing, Stitching, Animating, Disassembling, and Feeding.

ANIMATING

actuated elastomers

Omar Khan uses mechanically operated sensing to make assemblies that respond to changes in the atmospheric conditions of their surroundings. A sensor measures levels of carbon dioxide in the vicinity. When it registers a certain programmed threshold, it sends a signal to a series of actuators that raise or lower flexible conical chambers. These chambers, made from composite urethane elastomers, fill up a given space, to disperse a crowd, thereby lowering carbon dioxide levels.

actuated elastomers

Omar Khan

Omar Khan uses mechanically operated sensing to make assemblies that respond to changes in the atmospheric conditions of their surroundings. A sensor measures levels of carbon dioxide in the vicinity. When it registers a certain programmed threshold, it sends a signal to a series of actuators that raise or lower flexible conical chambers. These chambers, made from composite urethane elastomers, fill up a given space, to disperse a crowd, thereby lowering carbon dioxide levels.

FEEDING

algae-laden hydrogels

Assia Crawford embeds clay and ceramics with living matter, or metabolically active microalgae (Chlorella vulgaris). Working within a carefully maintained algae control room, Crawford and her team propagate various strains and monitor their growth in clay substrates of different makeups. The grown algae strains are centrifuged into a dense slurry, which is mixed with a gelling agent to produce a hydrogel. This gel is then painted onto 3D-printed clay vessels filled with nutrient-enriched water. To cultivate the algae, Crawford and her team spray the vessels with deionized water once a day and place them under growth lights overnight. The resulting building blocks can be interlocked to form partitions, integrating metabolic processes, namely photosynthesis, into otherwise abiotic assemblies, with the possibility of sequestering CO2.

algae-laden hydrogels

Assia Crawford

Assia Crawford embeds clay and ceramics with living matter, or metabolically active microalgae (Chlorella vulgaris). Working within a carefully maintained algae control room, Crawford and her team propagate various strains and monitor their growth in clay substrates of different makeups. The grown algae strains are centrifuged into a dense slurry, which is mixed with a gelling agent to produce a hydrogel. This gel is then painted onto 3D-printed clay vessels filled with nutrient-enriched water. To cultivate the algae, Crawford and her team spray the vessels with deionized water once a day and place them under growth lights overnight. The resulting building blocks can be interlocked to form partitions, integrating metabolic processes, namely photosynthesis, into otherwise abiotic assemblies, with the possibility of sequestering CO2.

FEEDING

biocalcified foam

The translation of organic matter into a building product is often punctuated by an act of killing, such as felling a tree for lumber. In her research, Aurelie Mosse induces chemical reactions with living matter, mainly bacteria, that result in both its death and a structural byproduct. In Papier Plume, paper waste is ground into pulp and mixed with a resin-based foaming agent, starch glue, and water to form a foam. This foam is then poured into a mold and left to air dry. Once dry, the foam sheet is submerged within a solution of Sporosarcina pasteurii, allowing the bacteria to be fully absorbed by the foam. In the final step, the sample gains rigidity as it is soaked in a calcifying solution. This causes the bacteria to form a dense matrix of calcite, entombing it and ultimately leading to apoptosis. In this sense, the workflow depends on the biochemical reactions of an animate input, the bacterial colony, which culminates in de-activating them to achieve the material’s use state. The labor of sustaining this live stock–maintaining proper conditions and feeding schedules–is put toward its de-animation.

biocalcified foam

Aurelie Mosse

The translation of organic matter into a building product is often punctuated by an act of killing, such as felling a tree for lumber. In her research, Aurelie Mosse induces chemical reactions with living matter, mainly bacteria, that result in both its death and a structural byproduct. In Papier Plume, paper waste is ground into pulp and mixed with a resin-based foaming agent, starch glue, and water to form a foam. This foam is then poured into a mold and left to air dry. Once dry, the foam sheet is submerged within a solution of Sporosarcina pasteurii, allowing the bacteria to be fully absorbed by the foam. In the final step, the sample gains rigidity as it is soaked in a calcifying solution. This causes the bacteria to form a dense matrix of calcite, entombing it and ultimately leading to apoptosis. In this sense, the workflow depends on the biochemical reactions of an animate input, the bacterial colony, which culminates in de-activating them to achieve the material’s use state. The labor of sustaining this live stock–maintaining proper conditions and feeding schedules–is put toward its de-animation.

DISASSEMBLING

biogel sheets

![]()

![]()

From metals to concrete, most building materials are inorganic and therefore break down over time only through mechanical or chemical weakening of their structure. Sutherlin Santo uses plant-based starch matter to make biodegradable materials with a range of mechanical and visual properties. In their experiments, the biopolymer gel is fed into a paste extruder on a robot arm and printed through predetermined tool paths into multi-layered sheets with variable rigidity and opacity. The practice has used this process to produce elements across a range of scales, from tile-sized samples to a stool to a wall-cladding system. The decomposition of these various components can be induced through biodegradation, a process which harnesses the digestion of microorganisms to break up the material structure of the biogel.

biogel sheets

Sutherlin Santo

From metals to concrete, most building materials are inorganic and therefore break down over time only through mechanical or chemical weakening of their structure. Sutherlin Santo uses plant-based starch matter to make biodegradable materials with a range of mechanical and visual properties. In their experiments, the biopolymer gel is fed into a paste extruder on a robot arm and printed through predetermined tool paths into multi-layered sheets with variable rigidity and opacity. The practice has used this process to produce elements across a range of scales, from tile-sized samples to a stool to a wall-cladding system. The decomposition of these various components can be induced through biodegradation, a process which harnesses the digestion of microorganisms to break up the material structure of the biogel.

RE-FUSING

bioregional building products

![]()

![]()

Industrial building products are often sourced from major manufacturing regions, and their long-distanced transportation to construction sites accounts for a substantial share of their embodied carbon. Moreover, the differences in the material composition of products are mainly the result of industry standards and regulatory regimes, rather than the outcomes of regional variation of stock, like local tree species and geological substrate. For the Lot 8 project at LUMA Arles, Assemble, Atelier LUMA, and bc architects sought to initiate a different relationship between the process of building and the material economies of the project's locality. Rather than relying on transcontinental supply chains, they sourced and processed nearly all of the materials for the project within 70km of the site. Within the building process, demolished material was, where possible, fed back into new construction. Terracotta tiles that fell off an extant roof were crushed, mixed with lime stripped from the building’s original walls, and applied to patch existing damage. Rice straw and sunflower stems harvested from the area were bundled and embedded within wall assemblies as thermal and acoustic insulation. In this way, construction became a means of testing and refining local recipes, rather than implementing a set of standardized finishes predetermined by a specification document.

bioregional building products

Assemble, Atelier LUMA, bc architects

Industrial building products are often sourced from major manufacturing regions, and their long-distanced transportation to construction sites accounts for a substantial share of their embodied carbon. Moreover, the differences in the material composition of products are mainly the result of industry standards and regulatory regimes, rather than the outcomes of regional variation of stock, like local tree species and geological substrate. For the Lot 8 project at LUMA Arles, Assemble, Atelier LUMA, and bc architects sought to initiate a different relationship between the process of building and the material economies of the project's locality. Rather than relying on transcontinental supply chains, they sourced and processed nearly all of the materials for the project within 70km of the site. Within the building process, demolished material was, where possible, fed back into new construction. Terracotta tiles that fell off an extant roof were crushed, mixed with lime stripped from the building’s original walls, and applied to patch existing damage. Rice straw and sunflower stems harvested from the area were bundled and embedded within wall assemblies as thermal and acoustic insulation. In this way, construction became a means of testing and refining local recipes, rather than implementing a set of standardized finishes predetermined by a specification document.

DISASSEMBLING

delaminated lumber

![]()

![]()

In traditional lumber, individual dimensioned units (such as 2’x4’) are extracted from harvested logs, leaving behind substantial remnant wood that is discarded as waste. HANNAH has employed kerfing techniques, which apply a series of spaced cuts, to utilize entire logs. In their project Unlog, a robotic mill cuts a log lengthwise in an alternating pattern that allows the log to unravel like an accordion. The cut paths can be adjusted to follow the natural curvature of a log, allowing the technique to be used on a wider array of inventory. The logs are cut off site, transported in their collapsed, original form, and then stretched on site into A-frame structures. This process can occur in the other direction, too–the logs can be refolded back into their compact form and transported to other sites.

delaminated lumber

HANNAH

In traditional lumber, individual dimensioned units (such as 2’x4’) are extracted from harvested logs, leaving behind substantial remnant wood that is discarded as waste. HANNAH has employed kerfing techniques, which apply a series of spaced cuts, to utilize entire logs. In their project Unlog, a robotic mill cuts a log lengthwise in an alternating pattern that allows the log to unravel like an accordion. The cut paths can be adjusted to follow the natural curvature of a log, allowing the technique to be used on a wider array of inventory. The logs are cut off site, transported in their collapsed, original form, and then stretched on site into A-frame structures. This process can occur in the other direction, too–the logs can be refolded back into their compact form and transported to other sites.

STITCHING

felted fiber

Hair is a ubiquitous, naturally occurring material, associated with numerous techniques of styling and shaping. Felecia Davis adapts these to a scale beyond the individual body, focusing on one type of hair styling, locking or dreadlock. This technique, belonging to a tradition of Black cultural practices, involves twisting hair until it forms a thickened mass, or a lock. Because it follows a regular motion of twisting, this process can be translated into a rule-based grammar, which allows it to be written as a computerized code. Davis then uses this code to direct a knitting machine to weave fiber into isocords of wool yarns, which are then felted. As the fibers are felted the cords gain durability and structural potential.

felted fiber

Felecia Davis

Hair is a ubiquitous, naturally occurring material, associated with numerous techniques of styling and shaping. Felecia Davis adapts these to a scale beyond the individual body, focusing on one type of hair styling, locking or dreadlock. This technique, belonging to a tradition of Black cultural practices, involves twisting hair until it forms a thickened mass, or a lock. Because it follows a regular motion of twisting, this process can be translated into a rule-based grammar, which allows it to be written as a computerized code. Davis then uses this code to direct a knitting machine to weave fiber into isocords of wool yarns, which are then felted. As the fibers are felted the cords gain durability and structural potential.

STITCHING

fiber-rich earthen textile

Most textiles, in wearable and architectural applications, now contain synthetic fiber reinforcement. These fibers are often petroleum-based, with a substantially higher carbon footprint than organic or biotic fibers. Lola Ben Alon mixes geo-materials with bio-fibers to create feedstock for 3D-printed structures that may achieve similar strength to synthetic textiles. The introduction of vegetative fibers and other biopolymers, including agro-waste products, into clay rich soils can improve ductility and thermal resistivity of the fabricated building assemblies, from mass-insulation walls to paper-thin partitions.

fiber-rich earthen textile

Lola Ben Alon

Most textiles, in wearable and architectural applications, now contain synthetic fiber reinforcement. These fibers are often petroleum-based, with a substantially higher carbon footprint than organic or biotic fibers. Lola Ben Alon mixes geo-materials with bio-fibers to create feedstock for 3D-printed structures that may achieve similar strength to synthetic textiles. The introduction of vegetative fibers and other biopolymers, including agro-waste products, into clay rich soils can improve ductility and thermal resistivity of the fabricated building assemblies, from mass-insulation walls to paper-thin partitions.

RE-FUSING

fired-on-site masonry

![]()

![]()

Masonry materials like brick are typically fired at a production facility before they are transported to the construction site. In this setup, about 40% of the heat generated in the firing process is absorbed by the kiln itself. Anupama Kundoo recuperates some of this energy loss and employs labor within local economies by building structures out of un-fired mud and baking them in situ to complete their construction. In her Volontariat Homes project, a series of domed houses were built in Pondicherry, India with mud bricks and mud mortar. Additional bricks and other mud products such as tiles and kitchenware were placed in the house interiors. The houses and their contents were then fired into conventional brick and ceramics, gaining material strength and durability.

fired-on-site masonry

Anupama Kundoo

Masonry materials like brick are typically fired at a production facility before they are transported to the construction site. In this setup, about 40% of the heat generated in the firing process is absorbed by the kiln itself. Anupama Kundoo recuperates some of this energy loss and employs labor within local economies by building structures out of un-fired mud and baking them in situ to complete their construction. In her Volontariat Homes project, a series of domed houses were built in Pondicherry, India with mud bricks and mud mortar. Additional bricks and other mud products such as tiles and kitchenware were placed in the house interiors. The houses and their contents were then fired into conventional brick and ceramics, gaining material strength and durability.

ANIMATING

hygromorphic wood sheets

Like many structural systems, shell structures often require complex manufacturing and formwork, as well as intricate on-site logistics to assemble them. Components must be machine-manufactured to a specific shape and then, once they’ve reached the building site, lifted into place piece by piece, demanding immense energy expenditure and physical force. Dylan Wood lessens these demands by working with the inherent hygromorphic properties of wood to craft structural sheets that unfold through air drying into their intended curved geometry once they are brought onto the construction site. Wood uses a board-specific algorithmic calculation of curvature potential to model each surface in advance of construction, allowing interlocks to be set without formwork or external mechanical force and little onsite work. This method has been used to produce lightweight, long-span roof structures.

hygromorphic wood sheets

Dylan Wood

Like many structural systems, shell structures often require complex manufacturing and formwork, as well as intricate on-site logistics to assemble them. Components must be machine-manufactured to a specific shape and then, once they’ve reached the building site, lifted into place piece by piece, demanding immense energy expenditure and physical force. Dylan Wood lessens these demands by working with the inherent hygromorphic properties of wood to craft structural sheets that unfold through air drying into their intended curved geometry once they are brought onto the construction site. Wood uses a board-specific algorithmic calculation of curvature potential to model each surface in advance of construction, allowing interlocks to be set without formwork or external mechanical force and little onsite work. This method has been used to produce lightweight, long-span roof structures.

DISASSEMBLING

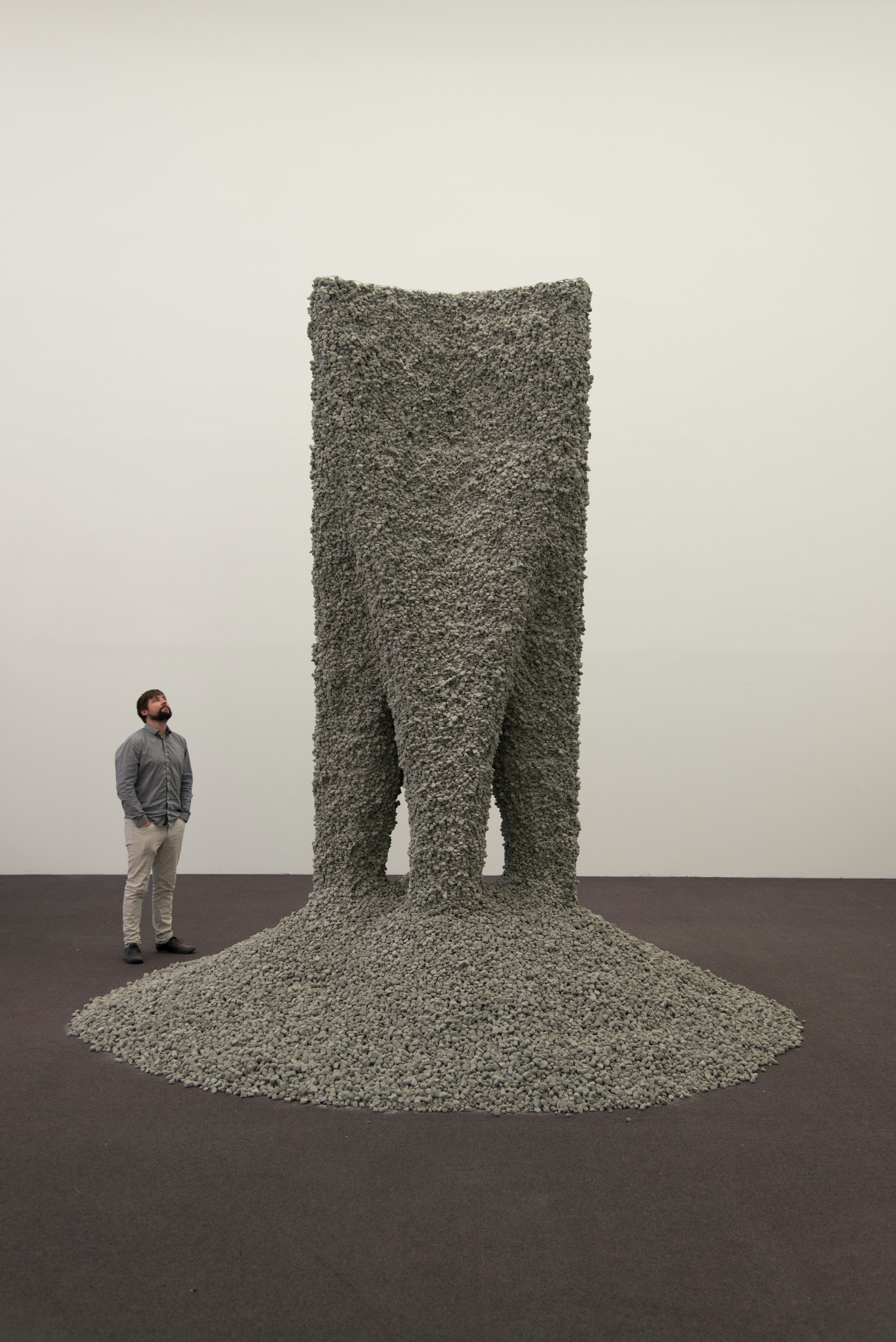

jammed gravel

![]()

![]()

Aggregate materials rely on the addition of a binding agent to become structurally efficient, such as chemical binders and mechanical fasteners. In the case of concrete, cement triggers an irreversible chemical transformation when combined with water or carbon dioxide as it sets, hardens, and adheres to aggregates like sand and gravel. Gramazio Kohler explores a different, reversible method for holding aggregate together. In the projects Rock Print and Rock Print Pavilion, a robot arm unspools twine between layers of loose gravel. As the layers accumulate vertically, the coils of twine provide enough additional friction for the aggregate to hold itself together under its own weight. This technique, called jamming, temporarily fixes the otherwise fluid material into an array of irregular, yet structurally sound forms. Unlike typical binders, the twine’s hold on the aggregate is reversible–the twine can be re-coiled, causing the aggregate to collapse back into a loose pile, returning to a fluid state, unchanged from its material composition before use.

jammed gravel

Gramazio Kohler

Aggregate materials rely on the addition of a binding agent to become structurally efficient, such as chemical binders and mechanical fasteners. In the case of concrete, cement triggers an irreversible chemical transformation when combined with water or carbon dioxide as it sets, hardens, and adheres to aggregates like sand and gravel. Gramazio Kohler explores a different, reversible method for holding aggregate together. In the projects Rock Print and Rock Print Pavilion, a robot arm unspools twine between layers of loose gravel. As the layers accumulate vertically, the coils of twine provide enough additional friction for the aggregate to hold itself together under its own weight. This technique, called jamming, temporarily fixes the otherwise fluid material into an array of irregular, yet structurally sound forms. Unlike typical binders, the twine’s hold on the aggregate is reversible–the twine can be re-coiled, causing the aggregate to collapse back into a loose pile, returning to a fluid state, unchanged from its material composition before use.

FEEDING

mycelium column

Many building techniques employ temporary scaffolding to support the primary material while it cures and gains structural integrity. In common practices like concrete pouring, once the material sets, the formwork is removed and discarded. Growing Scaffold adapts this subtractive shaping and disposal by re-interpreting the formwork as a matrix through which living matter grows into a structural component such as a column. In this case knitted textile is seeded with mycelium, a network of filaments, hyphae, that compose the vegetative parts of fungus. As the mycelium grows through the knitted formwork, it feeds off the fiber. In this way, the formwork is subsumed by the living material, providing food for it, which causes it to grow following the geometry of the formwork. As living matter, the mycelium depends on careful cultivation, including the dispensation of nutrients and the monitoring of temperature, humidity, and light conditions. Yogiaman partners with Mycotech, a biotechnology company, to provide the labor required to sustain the mycelium as material stock.

mycelium column

Christine Yogiaman

Many building techniques employ temporary scaffolding to support the primary material while it cures and gains structural integrity. In common practices like concrete pouring, once the material sets, the formwork is removed and discarded. Growing Scaffold adapts this subtractive shaping and disposal by re-interpreting the formwork as a matrix through which living matter grows into a structural component such as a column. In this case knitted textile is seeded with mycelium, a network of filaments, hyphae, that compose the vegetative parts of fungus. As the mycelium grows through the knitted formwork, it feeds off the fiber. In this way, the formwork is subsumed by the living material, providing food for it, which causes it to grow following the geometry of the formwork. As living matter, the mycelium depends on careful cultivation, including the dispensation of nutrients and the monitoring of temperature, humidity, and light conditions. Yogiaman partners with Mycotech, a biotechnology company, to provide the labor required to sustain the mycelium as material stock.

DISASSEMBLING

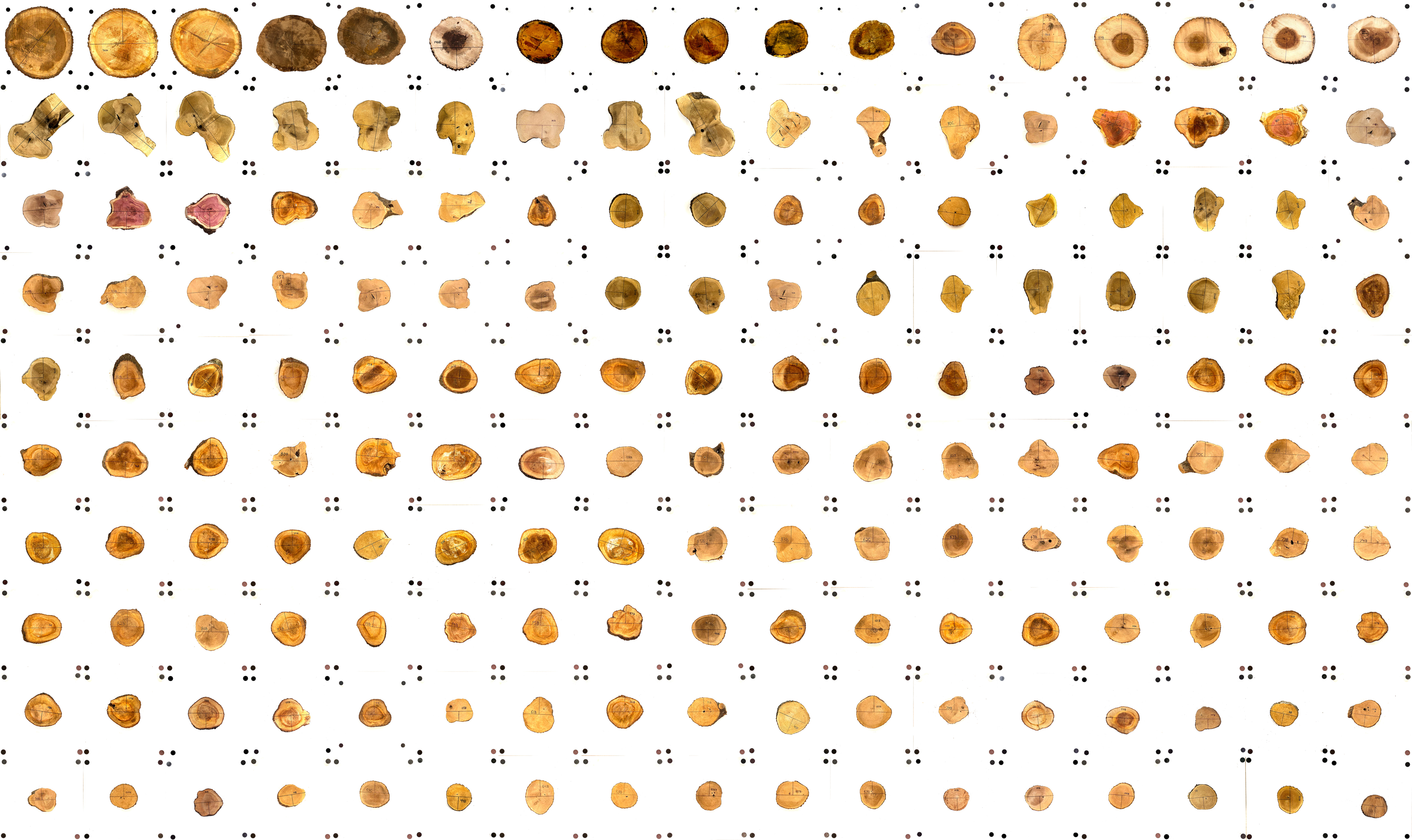

nondimensional lumber

![]()

![]()

In North America, wood most often makes its way into building applications as dimensioned lumber, made from harvested timber hewn and milled into units of standard size. This industrialized process links the value of wood to its ability to be standardized. Converting timber to lumber can be a wasteful process, as irregularly shaped and infested timber is converted to waste, shredded for chips or pulp or discarded outright. After Architecture’s project Tangential Timber enacts an alternative workflow that exploits the capacities of non-dimensional lumber. The process begins by collecting irregular waste wood and cutting it into disc-like cross sections of uniform thickness, called “cookies”. These cookies are digitized as images and then fed into a parametric script that aggregates and interlocks the digital cookies into three-dimensional forms such as vaults. Because they are joined without binders or hardware, the cookies can be disassembled while retaining their structural capacity.

nondimensional lumber

After Architecture

In North America, wood most often makes its way into building applications as dimensioned lumber, made from harvested timber hewn and milled into units of standard size. This industrialized process links the value of wood to its ability to be standardized. Converting timber to lumber can be a wasteful process, as irregularly shaped and infested timber is converted to waste, shredded for chips or pulp or discarded outright. After Architecture’s project Tangential Timber enacts an alternative workflow that exploits the capacities of non-dimensional lumber. The process begins by collecting irregular waste wood and cutting it into disc-like cross sections of uniform thickness, called “cookies”. These cookies are digitized as images and then fed into a parametric script that aggregates and interlocks the digital cookies into three-dimensional forms such as vaults. Because they are joined without binders or hardware, the cookies can be disassembled while retaining their structural capacity.

RE-FUSING

printed adobe

Adobe is a technique of earthen construction that has been used for centuries in many regions around the world. In the American Southwest, adobe construction is traditionally performed by hand, by setting adobe blocks with adobe mortar. In various projects in Colorado and New Mexico, Rael San Fratello has developed a mechanized workflow with adobe by deploying it as input for large-format 3D printing. The outcomes of this process gain structural capacity not through the aggregation of discrete units (as in traditional adobe block construction) but rather through the continuous folding of the extruded adobe onto itself in a gestural pattern. The printing apparatus is mobile enough to be carried onto a site, where local soils can be harvested and fed into the printing pump.

printed adobe

Rael San Fratello

Adobe is a technique of earthen construction that has been used for centuries in many regions around the world. In the American Southwest, adobe construction is traditionally performed by hand, by setting adobe blocks with adobe mortar. In various projects in Colorado and New Mexico, Rael San Fratello has developed a mechanized workflow with adobe by deploying it as input for large-format 3D printing. The outcomes of this process gain structural capacity not through the aggregation of discrete units (as in traditional adobe block construction) but rather through the continuous folding of the extruded adobe onto itself in a gestural pattern. The printing apparatus is mobile enough to be carried onto a site, where local soils can be harvested and fed into the printing pump.

STITCHING

reindeer sinew and fish stomachs

Skievvar recovers and adapts an indigenous practice by the oceangoing Sámi people of the region encompassing northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland. The technique—encountered by the artist in the archives of Norwegian scholar Just Knud Qvigstad—uses dried halibut stomachs as windows screens. Called skievvarcoalli, these windows are made by drying, oiling, and stretching harvested halibut sinew across wooden frames, and are typically used in outhouses and other simple buildings. Informed by indigenous handicraft (duodji) Nango and Utso Bongo prepare everyday items utilizing halibut stomach lining and reindeer sinew sourced from the region.

reindeer sinew and fish stomachs

Joar Nango, Sara Inga Utsi Bongo

Skievvar recovers and adapts an indigenous practice by the oceangoing Sámi people of the region encompassing northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland. The technique—encountered by the artist in the archives of Norwegian scholar Just Knud Qvigstad—uses dried halibut stomachs as windows screens. Called skievvarcoalli, these windows are made by drying, oiling, and stretching harvested halibut sinew across wooden frames, and are typically used in outhouses and other simple buildings. Informed by indigenous handicraft (duodji) Nango and Utso Bongo prepare everyday items utilizing halibut stomach lining and reindeer sinew sourced from the region.

ANIMATING

responsive bimetal

![]()

![]()

Many buildings are embedded with ways of responding to changes in their environment. These mechanical or digital systems typically operate through electrical circuitry, which sends inputs as signals to a central processing unit that in turn initiates a pre-programmed response–such as the lowering of a shading device or the activation of a heating source. Doris Sung’s research offers a model of responsiveness in building assemblies that does not require electrification or monitoring systems, relying instead on the innate behaviors of materials. In her work, Sung layers two thin sheets of different metal alloys, each with a different coefficient of expansion, producing a laminated bimetal. As temperatures increase, one side of the lamination expands more than the other, causing the material to curl. In some projects, these laminated pieces are hung from a supporting scaffold to produce a screen that, during the warmest parts of the day, heats up and transforms to block exterior light.

responsive bimetal

Doris Sung

Many buildings are embedded with ways of responding to changes in their environment. These mechanical or digital systems typically operate through electrical circuitry, which sends inputs as signals to a central processing unit that in turn initiates a pre-programmed response–such as the lowering of a shading device or the activation of a heating source. Doris Sung’s research offers a model of responsiveness in building assemblies that does not require electrification or monitoring systems, relying instead on the innate behaviors of materials. In her work, Sung layers two thin sheets of different metal alloys, each with a different coefficient of expansion, producing a laminated bimetal. As temperatures increase, one side of the lamination expands more than the other, causing the material to curl. In some projects, these laminated pieces are hung from a supporting scaffold to produce a screen that, during the warmest parts of the day, heats up and transforms to block exterior light.

RE-FUSING

waste plastic cladding

![]()

![]()

Post Rock's work is informed by the discovery of plastiglomerate, a new type of rock composite that has entered our planet's sedimentary record. Formed of plastics, sedimentary grain, and other debris, plastiglomerates challenge the traditional dyad of “natural” and “unnatural” materials as the rock composite incorporates both. Attempting to simulate these geological processes, Post Rock fuses plastic waste diverted from auto manufacturing in the Detroit-region into building components. They process the collected plastic waste two ways: on site, where it is stacked and thermocast, and in the lab, where it is placed in a rotating thermoforming mold, which gives it the mold’s shape. In some cases, the outcomes of this workflow retain traces of the particular batch of waste plastic, leading to variability in color and texture in the finished product. Noting the regional specificity of waste streams, Post Rock speculates that different “geographies” of waste plastics and specificity could inform or result in differing composite material to be cast into architectural components.

waste plastic cladding

Post Rock

Post Rock's work is informed by the discovery of plastiglomerate, a new type of rock composite that has entered our planet's sedimentary record. Formed of plastics, sedimentary grain, and other debris, plastiglomerates challenge the traditional dyad of “natural” and “unnatural” materials as the rock composite incorporates both. Attempting to simulate these geological processes, Post Rock fuses plastic waste diverted from auto manufacturing in the Detroit-region into building components. They process the collected plastic waste two ways: on site, where it is stacked and thermocast, and in the lab, where it is placed in a rotating thermoforming mold, which gives it the mold’s shape. In some cases, the outcomes of this workflow retain traces of the particular batch of waste plastic, leading to variability in color and texture in the finished product. Noting the regional specificity of waste streams, Post Rock speculates that different “geographies” of waste plastics and specificity could inform or result in differing composite material to be cast into architectural components.